Chapter 8

Bungling at U.N.Instrument

of accession executed by Maharaja Hari Singh was similar to such instruments

executed by the rulers of other acceding states. There was no scope for

ifs and buts in it. According to it the accession was full, final and irrevocable

and not in any way conditional or provisional. It should have, therefore,

settled the questions of future of Jammu and Kashmir state once for all.

The problem created by Pak invasion could be effectively tackled by the

Indian armed forces.

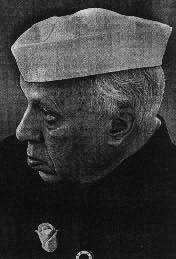

Pandit

Jawahar Lal Nehru

But one blunder

of Pt. Nehru virtually undid what accession had achieved. Lord Mountbatten

as constitutional head of the state wrote a letter to Hari Singh on October

27 in which he mooted the question of ascertaining the wishes of the people

of the state about accession to India after the Pak invaders were thrown

out. This letter was followed by a statement by Pt. Nehru to the same effect.

It was a grave blunder ramification of which have continued to cloud and

complicate an issue which was legally and constitutionally settled by the

acceptance of the accession of the Jammu and Kashmir state to India on

October 26, 1947. This reminds one of the well known couplet:

Woh Waqt bhi

dekha hai

Tareekh ke

gaharaiyon men,

Lamhon ne

khata ki

Sadion ne

saza pai.

"Mistake committed

at the spur of a moment proved to be a curse and punishment for centuries."

The offer of

plebiscite was uncalled for, irrelevant to the situation and illegal. There

was no provision in the instrument of Accession about it. It was outside

the ambit of the Act of Indian Independence of the British Parliament.

It was never accepted by the Maharaja who had absolute choice in the matter.

Nor was it demanded by Sh. Abdullah or any other leader of the State.

The argument

that Indian leaders were guided by the situation in Junagarh and Hyderabad

in making their offer is untenable because there was no analogy between

those states and the situation obtaining in Kashmir. Both Junagarh and

Hyderabad were not only overwhelmingly Hindu in population but also completely

surrounded on all sides by Indian territory. Therefore under the Mountbatten

plan they had no other choice but to accede to India. The only plausible

explanation therefore is that Lord Mountbatten made the suggestion about

plebiscite merely to placate Pakistan and Pt. Nehru accepted it for the

same reason. It was in keeping with his policy of appeasement of Muslim

League and Pakistan. Later, however, other explanation: such as refutation

of the two-nation theory by showing that a Muslim majority area was prepared

to remain in India of its own free will and thereby strengthening of secularism

in India have also been offered. But they are after thoughts.

This blunder

provided Mr. Jinnah with an opportunity to politicize and internationalize

the military issue and convert his impending defeat on the battle field

into an eventual political and diplomatic victory. He sent a message to

Lord Mountbatten through Field Marshal Auchinleck on the 29th October,

1947 to meet him in conference at Lahore. It was a clever and astute move

to make the issue political while the invasion was still on and the possible

military decision could not be in his favor.

Sardar Patel,

a realist and a practical man as he was, saw through Mr. Jinnah's game.

He opposed any Indian leader going to Lahore and warned against appeasing

Mr. Jinnah who was clearly the aggressor in Kashmir. He suggested that

if Mr. Jinnah wanted to discuss anything, he could come down to Delhi.

But his wise counsel was not heeded and Lord Mountbatten and Pt. Nehru

got ready to fly to Lahore on the 1st of November. Pt. Nehru, however,

had to drop out at the last moment due to indisposition.

At the Conference

Table Mr. Jinnah proposed that both sides should withdraw from Kashmir.

When Lord Mountbatten asked him to explain how the tribesman could be induced

to remove themselves Mr. Jinnah replied: "If you do this, I will call the

whole thing off." This made it absolutely clear that the so-called tribal

invasion was fully organized and controlled by the Pakistan Government.

Lord Mountbatten

formally made the offer of plebiscite to Mr. Jinnah at this Conference.

Mr. Jinnah objected that with Indian troops in their midst and with Sh.

Abdullah in power, the people of Kashmir would be far too frightened to

vote for Pakistan. Therefore Lord Mountbatten suggested a plebiscite under

the auspices of the U.N.O. This was a clear victory for Mr. Jinnah. He

had virtually got the effect of legal accession of the State to India nullified

and got Lord Mountbatten committed to a course of action which could only

internationalize an issue in which strictly speaking Pakistan had no locus

standi after the Maharaja had signed the Instrument of Accession and the

Government of India had accepted it.

Pt. Nehru ratified

the offer verbally made by Lord Mountbatten at Lahore in his broadcast

speech of November 2, 1947 in which he declared his readiness, after peace

and rule of law had been established, to have a referendum held under some

international auspices such as that of the United Nations.

The commitment

on the part of the Government of India had, besides throwing the accession

of Kashmir to India open to question, two other important implications.

On the one hand it provided Pakistan with a second string to its bow. Conscious

of the strength of the appeal of religion to Muslims, it could now hope

to secure by the peaceful method of plebiscite what it failed to achieve

by force. On the other hand, it made the Government of India dependent

for the ratification of the accession through plebiscite on the goodwill

of Sheikh Abdullah whose position was changed from that of a suppliant

to that of an arbiter who must be kept in good humor at all costs. These

in their turn set in motion a chain of events and created a psychological

atmosphere in Kashmir which suited Pakistan.

Even this major

concession which gave Pakistan a whip hand in Kashmir, did not soften the

attitude of Mr. Jinnah and his Government who kept up their military pressure

through tribal hordes supported by regular Pakistani troops at a high pitch.

Even though the invaders had been thrown out of the valley, they maintained,

as described earlier, their advance in Jammu and the northern areas of

the State. The right and honorable course for India in the circumstances

was to discontinue all negotiations with Pakistan and concentrate on securing

a military decision. India, at that time, was definitely in a position

to secure a favorable military decision had it decided to attack the bases

of the invaders in Pakistan. But Pt. Nehru in his anxiety to keep the conflict

confined to Jammu & Kashmir State would not permit that. In this he

had the full support of the Governor General, Lord Mountbatten. Therefore,

the negotiations were continued even when Pakistani invaders were wantonly

attacking and occupying more and more territory.

Direct talks

between Pt. Nehru and Mr. Liaqat Ali Khan, the Prime Minister of Pakistan,

were held for the first time since Pakistani invasion began, on December

8, 1947 when the former visited Lahore along with Lord Mountbatten to attend

a meeting of the Joint Defense Council. But they proved abortive. Therefore

Lord Mountbatten who was growing apprehensive of the fighting in Kashmir

degenerating into full scale war between the two Dominions, a contingency

which he wanted to avoid at all costs, pressed Pt. Nehru to refer the matter

to the U.N.O. and invoke its good offices for a peaceful settlement of

the problem.

Appeal to U.N.O.

Most of Pt.

Nehru's Cabinet colleagues were opposed to this suggestion for obvious

reasons. It amounted to inviting outside interference into a purely internal

and domestic problem and a tacit admission on the part of India of its

inability and incapacity to meet the situation created by the invaders.

But ultimately he had his way.

As a necessary

preliminary, he personally handed over a letter of complaint to Mr. Liaqat

Ali Khan on December 22, 1947 when the latter visited Delhi in connection

with another meeting of the Joint Defense Gouncil. It demanded that Pakistan

should deny to the invaders (i) all access to and use of Pakistan territory

for operations against Kashmir (ii) all military and other supplies and

(iii) all other kinds of aid that might tend to prolong the struggle.

Liaqat Ali

Khan promised to send an early reply. But instead of doing that a fresh

invasion was launched in Jammu which forced an Indian brigade to fall back

to Nowshera from Jhangar, an important road junction in the western part

of Jammu region. The pressure on areas still nearer to Jammu city was also

stepped up. This made attack on the enemy bases in Pakistan an imperative

necessity to save Jammu and the supply line to Srinagar. But Pt. Nehru

was unwilling to do that. So, without waiting for a reply from Pakistan

which was being deliberately delayed, the Government of India formally

appealed to the U.N.O. under C'hapter 35 of the U.N. Charter on December

31, 1947 and nominated Shri Gopalaswamy Iyengar to lead the Indian Delegation

which was to include Sh. Abdullah also.

That very day,

but af ter the application to the U.N . Security Council had been despatched,

Liaqat Ali Khan's reply was received by the Government of India. It was

lengthy catalog of counter charges. It contained fantastic allegations

that the Government of India were out to destroy Pakistan, it also raised

the question of Jungarh. It gave clear indication of the line Pakistan

was going to take at the U.N.O. From the timing of the reply, it was evident

that Pakistan Government had its informers in the Indian Foreign Office

who kept it posted with the exact details of the Indian complaint and the

time of its despatch. This presence of Pakistani agents and informers in

the Indian Foreign Office is an advantage that continues to give Pakistan

an edge over India in diplomacy.

This appeal

to the U.N.O. by India was the second major blunder on her part in handling

of the Kashmir question and was a clear diplomatic victory for Pakistan

which succeeded in politicizing an issue in which she had no locus standi.

It came as a surprise not only to the Indian public but also to all those

countries which had been looking upon the Kashmir question as an internal

affair of India. No self-respecting country would have voluntarily invited

the interference of foreign powers through the U.N.O. in an essentially

domestic affair like this. In doing so, the Government of India simply

played into the hands of Pakistan whose leaders found in it a God-sent

opportunity to malign India before the bar of world opinion by levelling

all kind of fantastic and baseless charges against her.

The Security

Council immediately put the issue on its agenda and discussion on it began

on January 15, 1948. But to the great disappointment of the Government

of India, instead of giving precedence to the Indian complaint about Pakistan's

hand in the invasion and putting pressure on Pakistan to stop aiding the

invaders, the security council from the very beginning put India and Pakistan

the victim of aggression and the aggressor, on the same footing and began

to consider Pakistan's counter-charges, which were quite unrelated to the

basic issue, along with the question of Pak aggresion on Jammu & Kashmir.

This was clear from the resolution moved by the Council President Dr. Von

Langhenhare of Belgium on January 20, 1948. The resolution provided that (i) a Commission of the Security Council be established composed of the

representatives of three members of the United Nations, one to be elected

by India, one by Pakistan and the third to be designated by the two so

elected: (ii) the Commission shall proceed to Jammu & Kashmir as soon

as possible to investigate the facts and secondly to exercise any mediatory

influence likely to smoothen the difficulties and (iii) the Commission

shall perform functions in regard to the situation in Jammu & Kashmir

and secondly in regard to other situations set out by Pakistan foreign

Minister in the Security Council.

In spite of

the objections of the Indian delegation that by bringing cther extraneous

issues raised by Pakistan within the purview of the Commission, the Security

Council was relegating the real issue to the background, the resolution

was passed with nine in favor and two, USSR and Ukraine, abstaining.

As the debate

proceeded, the President suggested that the Security Council might concentrate

its attention on the question of holding a plebiscite. This was fully in

accordance with Pakistan's line and was therefore duly supported by her

Foreign Minister and chief delegate, Mr. Zaffarullah Khan. Thereafter resolutions

and proposals began to be framed with that end in view.

This provoked

the Chief Indian delegate, Mr. N. Gopala Swamy Ayyengar, to declare that

the Security Council was "putting the cart before the horse". The real

issue, he said, was to get the fighting in Jammu & Kashmir stopped

by pressing Pakistan to withdraw her support from the invaders. The question

of a plebiscite, he added could be taken up only when peace and normal

conditions had been restored. He further requested for adjournment of the

debates so that he might go back to India for further consultations. Even

this request for adjournment was opposed by most of the members of the

Security Council.

This hostile

attitude of the Security Council came as a rude shock to the Government

of India and disillusioned even Pt. Nehru who had insisted on reference

being made to the U.N.O. against the advice of his colleagues. Speaking

at Jammu on February 15, 1948 he said, "Instead of discussing and deciding

our references in a straight forward manner, the nations of the world sitting

in that body got lost in power politics.'

The pattern

of voting in the Security Council began to influence India's foreign policy

in favor of the bloc headed by the U.S.S.R. which further prejudiced the

Western countries against India in regard to the Kashmir question.

Causes of

India's Failure at U.N.

But it would

be wrong to put the whole blame for this near unanimous disregard of Indian

complaint on the power politics of the two blocs which was reflected in

their attitude and voting at the U.N. on invariably all issues. India's

handling and presentation of the Kashmir issue was so faulty, unrealistic

and incoherent from the very beginning that it could not evoke any better

response even from well meaning and really impartial delegates. This bungling

on the part of India in handling a straightforward issue because of the

mental cobwebs of Pt. Nehru must be clearly understood for appreciation

of the Kashmir problem as it has since developed inside and outside the U.N.O.

From the purely

Indian point of view it was, as said above, wrong to refer the Kashmir

issue to the U.N.O. It was a domestic issue. Pakistan had committed unprovoked

aggression. India was in a position to handle the situation militarily.

It should have been left to Pakistan to invoke the interference of the U.N.O. to escape the thrashing it deserved. But instead of putting Pakistan

in a tight position, India decided to put her own head in the noose. It

was utter bankruptcy of leadership as well as statesmanship.

Having taken

the decision to go to the U.N.O., the issue should have been put before

that body in its true perspective emphasising the fact of Pakistan's aggression

in Jammu and Kashmir State which had become an integral part of India after

accession in terms of the Mauntbatten Plan. India should have specifically

charged Pakistan of unprovoked aggression and not of mere abetment of aggression

by giving passage to tribal raiders through her territory. There was an

overwhelm ing evidence that the aggression had been committed by Pakistan

itself. By avoiding the specific charge of aggression in her complaint,

the Government of India compromised its own position before the Security

Council from the very beginning. Such a complaint could not create that

sense of urgency about the problem and the real issue of aggression in

the minds of Security Council members who were not supposed to know the

real situation and had, therefore, to be guided by the memoranda submitted

by the respeetive parties and their elucidation through the speeches in

the Council.

If the Indian

plaint was wrong in so far as it underplayed Pakistan's hand behind the

invasion, its advocacy was worse. The man chosen to lead the Indian delegation,

N. Gopala Swamy-Ayyengar, was a good old man who had been Prime Minister

of Jammu and Kashmir for some years before 1944. But he was a novice to

the ways of U.N. diplomacy which is conducted more at informal meetings

and late night dinners and drinking parties than at the Council table.

He was an honest gentleman who believed in the Indian concept of "early

to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise." He was

too honest and simple hearted to be a match for Pakistan's Zaffarullah

Khan, who, apart from being a leading jurist, was man of few scruples,

wide contacts and great eloquence. It is really surprising why Mehar Chand

Mahajan who as a jurist and a debater was more than a match for Pakistan's

Zaffrullah, was not chosen for the job. Being the Prime Minister of the

State during the days of Pakistani invasion, he was best suited to rebutt

the baseless charges and lies of Pakistan. The only explanation for this

lapse is that he was a persona non grata with Pt. Nehru who often gave

preference to his own likes and dislikes over the interests of his country.

To make things

worse, the Indian delegation included Sh. Abdullah, "a flamboyant personality"

about whom Campbell Johnson, the gifted press Attache of Lord Mountbatten,

had predicted that he would "Swamp the boat of India." He was more interested

in projecting himself and running down the Maharaja, who was the real legal

sanction behind Kashmir's accession to India, and Dogra Hindus than in

pleading the cause of India.

No wonder therefore

that the statements and speeches made by him on different occasions as

also the statements and speeches of Pt. Nehru provided Zafarullah with

the stick to beat India with.

Even more inexplicable

was the failure of the Indian spokesmen to lay proper stress on the fact

of accession by the Maharaja which in itself was full, final and irrevocable

and from which all the rights of the Government of India flowed. They harped

on the "will of the people of Kashmir" and India's offer to them to give

their verdict about the accession through a plebiscite after peace had

been restored there.

The members

of the Security Council as also world opinion in general had not been properly

educated regarding the true facts of the Kashmir situation. The external

publicity of the Government of India in this as in other matters was halting

and hesitating. The government of India itself appeared to be apologetic

about the acceptance of Kashmir's accession. It felt shy of telling to

the world the atrocities committed by Pakistani and local Muslims on the

Hindus of the State. It was as anxious to run down the Maharaja as were Sh. Abdullah and Pakistan. It wanted to build its case entirely on the

popular support of the people of Kashmir regarding the question of accession

rather than on the ract of accession itself.

The Pakistan

Government and its delegates at the U.N.O. on the other hand were aggressively

assertive about their baseless and unrelated charges against India and

blatantly emphatic in their denial of the Indian charge about aiding the

Tribal invaders. In the face of Pakistan's categorical denial and Government

of India's apologetic and hesitating approach the first impression on world

opinion as also on the U.N. circles was distinctly pro-Pakistan and anti-India.

Pakistan had

the added advantage of Gilgit on her side. The strategic importance of

Gilgit in the overall western strategy to contain Soviet Union was immense

and the British were fully conscious of it. Pakistan could treat it as

a bargaining counter to win the support of the Western bloc for itself.

The comparatively

favorable attitude of the Communist delegates toward India from the very

beginning had also something to do with Gilgit. Control of Gilgit and Kashmir

Valley by the Western Bloc through Pakistan was considered by Russia a

major threat to her armament industries which had been shifted during the

World War II to the east of the Ural Mountains. They were within easy reach

of Gilgit based bombers. This fact, coupled with the dominant position

of pro- Communist elements in Sh. Abdullah's Government who wanted to use

Kashmir as a spring-board for Communist revolution in India, influenced

Communist Russia to take the side she did. This in its turn helped Pakistan

to get further ingratiated with the Western Bloc which had the upper hand

in the Security C ouncil.

The pattern

that was set in the early debates in the Security Council was reflected

in the composition of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan-

UNCIP. India chose Czechoslovakia from the Com munist block and Pakistan

chose Argentina, and when Pakistan and India failed to agree about their

common nominee, the Council President named the USA. The Security Council

further decided to raise the strength of the UNCIP to five by nominating

two more members-Belgium and Colombia to it.

Pakistan insisted

that the Commission should also go into the question of Jungarh, genocide

and certain other prcblems arising out of the partition of India. The USA

and Britain helped Pakistan to get these issues discussed in the Security

Council. On June 3, 1948, the Council President submitted a resolution

which proposed that the commission be directed to proceed without delay

to the area of disput and besides the question of Jammu and Kashmir, study

and report to the Security Council when it considers appropriate, on the

matters raised in the letter of the Foreign Minister of Pakistan dated

January 15, 1948.

This resolution

was passed by the Security Council with USSR, Ukraine and Nationalist China

(Formosa) abstaining.

This widening

of the scope of the UNCIP evoked strong protests from the Indian delegation

and the Indian Government. It was even suggested that India should withdraw

its complaint from the UN and walk out of it. But, ultimately, the Government

of India agreed to receive the Commission and cooperate with it.

U.N. Imbroglio

The UNCIP arrived

in India on July 10, 1948 and began discussions with representatives of

India and Pakistan. The Pakistan Government which had so far denied any

complicity whatsoever in the invasion of Kashmir now found it impossible

to hide the facts any longer. Therefore, her Foreign Minister Zafarullah

Khan, informed the Commission that regular Pakistan troops had moved "into

certain defensive positions" in the State of Jammu & Kashmir. It created

an entirely new situation. It more than substantiated the original eomplaint

of India and clearly brought out Pakistan as an aggressor. It necessitated

a review of the situation "de novo." It put the question of plebiscite

which had been projected to the forefront by Pakistan in the Security Council

in the background for the time being and brought home to the Commission

the urgency of getting the hostilities stopped first, a point which India

had been stressing all along.

On August 13,

1948, the Commission, therefore, formulated and presented to the Government

of India and Pakistan a resolution which called upon both sides to stop

fighting which was to be followed by a Truce Agreement after which plebiscite

was to be conducted in the State under the auspices of a plebiscite administrator

to be appointed by the UN to determine the will of the people about the

acession of the State. It asked Pakistan to withdraw her troops as a first

step towards the creation of conditions in which plebiscite would be held.

India accepted

this resolution after obtaining certain clarifications as it vindicated

her stand that Pakistan being the aggressor must withdraw her troops first.

She particularly stressed the "end of early withdrawal of Pakistani troops

from the Northern areas where a garrison of State troops in the fort of

Askardu was still holding out against heavy odds.

Pakistan too

wanted certain clarifications particularly in regard to the position of

the so called "Azad Kashmir" Gcvernment which it had set up in the occupied

areas of the State. She also wanted to know the clarifications furnished

by the Commission to India and Indian acceptance of the clarifications

given by the Commission to her before she could accept the said resolution.

While Pakistan

was thus procastinating, the Commission returned to Geneva in September

1948 where it drew up its report which was submitted to the Security Council

in November 1948. It admitted in its report that admission by Pakistan

about the presence of her troops in Jammu & Kashmir and her overall

control of all Pakistani troops and Tribals fighting there had "confronted

the Commission with an unforeseen and entirely new situation". It therefore

recommended that as a first step toward the final solution of the dispute,

the Pakistan Government should be asked to withdraw its forces from the

State.

This has not

been done by Pakistan so far.

The Security

Coucil resumed its debate on Kashmir on November 25, 1948. It unanimously

appealed to India and Pakistan to stop fighting in Kashmir and do nothing

to aggravate the situation or endanger the current negotiations.

Following this

resolution Dr. Alfred Lozano, a member of the UNCIP, and Dr. Erik Colban,

personal representative of the UN Secretary General again visited New Delhi

and Karachi to discuss with the two Governments certain proposals supplementary

to the resolution of August 13, 1948. They dealt with appointment of a

Plebiscite Administrator and certain principles which were to govern the

holding of a plebiscite in Jammu and Kashmir after normal conditicns had

been restored.

Another round

of Conference between them and the Prime Minister of Inldia and Pakistan

followed, Pt. Nehru asked and obtained certain clarifications from Dr.

Lozano which were later published by India in the form of an aide memoire

setting out the Indian point of view in greater detail. Dr. Lozano returned

to New York on December 26, to report to the Security Council.

Soon after

he left, the Government of India without waiting for any further initiative

from the U.N.C.I.P. or the Security Council ordered a cease fire to be

operative from the midnight of January 1, 1949. Pakistan reciprocated.

This brought to an abrupt end the undeclared war between the two Dominions

which had continued for nearly 15 months.

|